The Thompson Elk Fountain:

A history of the patron, the sculptor, the architect, the early public reception, and the history since

Click here for UO Architecture Professor Keith Eggener’s more in-depth look at David P. Thompson and the sculpture.

Click here for historian Milo Reed’s look at the social history of the Thompson Elk Fountain in the decades since.

Share with historian Milo Reed your experiences of enjoying—or acts of free speech around—the Thompson Elk Fountain on Facebook and Twitter

Keith Eggner: Professor of Architecture, History, UO; Editor Emeritus, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians

Milo Reed: Chair, Oregon Commission on Historic Cemeteries; Black Cultural Library Advocate, Multnomah County Library and developer of “Our Story: Portland Through an African-American Lens” digital archive; Vanport Mosaic

David P. Thompson: shepherd to banker to politician to patron

David P. Thompson

In 1853 at age 19, David P. Thompson drove a herd of sheep from Harrison County, Ohio to Oregon City. He chopped wood and learned to survey land, eventually well enough to be “properly called the father of United States surveys in the Northwest.” By age 32, he became manager of the Oregon City Woolen Manufacturing Co., then the largest corporation of its kind in the Northwest. At 46, he cofounded Oregon’s first savings bank, eventually serving as the leader of 17 Northwest banks.

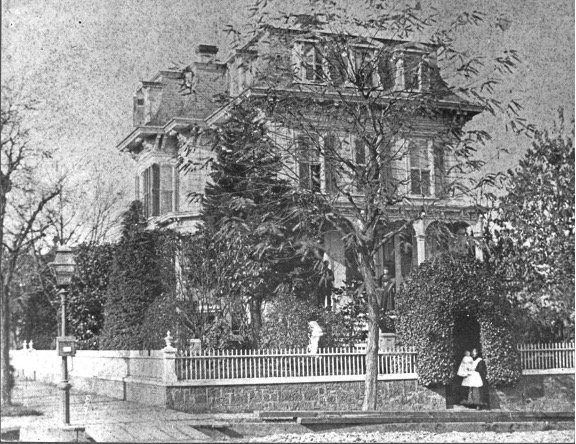

David P, Thompson House, Courtesy of Gholston Collection

As a public servant, Thompson enlisted in the Union Army and was a staunch abolitionist. He served as a county commissioner, an Oregon state legislator, and twice as an elector to the national Republican Party nominating James G. Blaine, an ardent supporter of Black suffrage. In 1887 and ’91, he successfully ran for Portland mayor. The Oregonian called his administration “efficient and vigorous.” Others thought he too often mingled business and politics. He was accused, but never convicted, of improprieties. In 1890, he ran for governor against Sylvester Pennoyer, a leading supporter of Chinese exclusion. He lost.

In other service, Thompson became the founding President and a lifetime member of the Oregon Humane Society. He co-founded and served as the first president of the Portland Public Library. He became a Regent of the University of Oregon and made substantial donations to build Woman’s Memorial Hall (now Gerlinger Hall). A Unitarian Church regent and firm believer in the hygienic benefits of cremation over burial, he cofounded the Portland Crematorium, which opened in Sellwood in April, 1901--the first crematorium west of the Mississippi River.

Early Elk Fountain, Courtesy of Gholston Collection

In 1899, inspired by Portland’s first work of public art, Skidmore Fountain, he proposed to the Mayor and City Council a “monument to Oregon Humane Society” to be “of benefit to humanity and the dumb animals . . .”

In 1901, age 67, Thompson embarked on trip around the world, but only got as far as Iowa where he became ill. He returned to Portland and soon after died of “pernicious anaemia”— stomach problems.

Roland Hinton Perry, Thompson Elk sculptor

The sculptor Roland Hinton Perry no doubt captured David P. Thompson’s eye with his most prominent commission, the “Court of Neptune Fountain,” for the Library of Congress’s Thomas Jefferson Building. Inspired by Rome’s Trevi Fountain, it features dramatic, neoclassical bronze renderings of Neptune, sea nymphs, turtles, frogs, tritons, dolphins, and seahorses, their muscles bulging as they appear to gallop through the spray. The sprawling piece was cast to Perry’s designs by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Co. of New York. The work was immediately and widely published in newspapers and magazines across the country, including The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Minneapolis Times, and The Architectural Record.

New photo: Roland Hinton Perry's “Court of Neptune Fountain," Library of Congress

Born in New York City in 1870, Perry went on to study sculpture and painting at the New York Art Students League, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Académies Julian and Delécluse in that same city. He ultimately received sculptural commissions in Harrisburg and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Buffalo, New York City, Washington D.C., Chattanooga, San Francisco, Louisville, and other places across the U.S. His paintings today can be seen at the Detroit Institute of Arts and other major museums. He died in 1941.

Perry’s work was cast by Henry-Bonnard Bronze Co. Bronze casting was still relatively new to the U.S., only having been introduced to this country in the mid-century. Staffed by French emigrés, Henry-Bonnard used the sand-casting method, as opposed to the lost-wax process more commonly associated with Italian foundries. Henry-Bonnard dominated bronze casting in turn-of-the-century America, serving as the favored foundry for such nationally renowned artists as Frederic Remington, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and Daniel Chester French.

Architect H. G. Wright, Thompson Elk Fountain architect

Fig. 4--The Oregonian, 1 Jan. 1900, p. 23

H.G. Wright arrived in Portland late in 1897, having left Moline, Illinois, where he had recently dissolved his monument design and manufacturing partnership. Wright was said to obtain all stones used in his work from Coskie and Son’s granite quarry in Barre, Vermont, the source for the Thompson Elk Fountain—and the identified source for the replacement parts for the fountain’s current rehabilitation.

Most of what we know about Wright comes from him. He specialized in “designing monuments, public fountains and mausoleums,” and claimed that “his designs today not only grace the different cities of his home state, but… they are found in many of the most prominent centers of the Eastern states.” Almost immediately upon arrival in Portland, Wright found high-profile work, for instance, a $5,000 memorial to Portland lawyer and former U.S. Senator Joseph Norton Dolph.

Whatever his other accomplishments, Wright remains best known for having designed, carved, and assembled the granite basin and pedestal of the Thompson Elk Fountain. In an advertisement, beneath a drawing of the still-uncompleted fountain, with Mt. Hood rising in the distance, Wright claims “The best MONUMENTAL WORK in the different cemeteries of Portland has been erected by me for its leading citizens. All the stone work is completed in our quarry by the most skilled workmen with the latest improved machinery. Have erected some of the best Monuments in nearly every State in the Union.”

Early reception of the Thompson Elk Fountain

Still from "My Private Idaho," Gus Van Sant's 1991 film

When the fountain was installed in 1900, Portland’s population stood at just over 90,000. Early reactions to the sculpture were mixed. A short piece published in August of that year reported that people had gathered at the fountain site to discuss “the question of why the elk… was furnished with such large antlers.” Said an early observer in The Oregonian, “Looks as if he hadn’t had a blade of grass… for 50 years… he does look gaunt, as if his home were in snowy woods, instead of this green plain.” Other observers were more impressed by what was seen as “a very fine piece of work, representing an elk standing ‘at gaze’ or in a position as if he had just heard the hounds baying on his track. His mane is as natural as life, and even the veins in his legs are showing.”

In recent decades a story has emerged that the Elks’ Club thought the Thompson Elk was an abomination, and reportedly refused a request to dedicate the fountain. One member purportedly called the elk a “monstrosity of art,” its legs too thin, its neck too long. It is not clear where this story originates. An extensive online search using a wide variety of search terms and databases--including Historic Oregon Newspapers, Newsbank, and The Oregonian Archives--turned up no evidence of the Elks’ rejection. The first description of the elk as a “monstrosity of art” appears to come from a story published in The Oregonian’s Northwest Magazine in 1983; one year later, the paper used the term “monstrosity of nature” with no specific attribution, supposedly as a historical description of the fountain. One thing the Elks’ Club did do—according to an Oregonian account of 1900—was conclude their Elks’ Day march through the city at the Thompson Fountain.

In 1974, the elk fountain was named a historical landmark. In perhaps a wry reference to Washington Park’s statue, “The Coming of the White Man,” the elk appeared with a bronze pointing Native American atop it, in Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, in 1991. In 2011, 2016, 2020, the elk statue and fountain were damaged by protestors, more out of exuberance than any apparent grudge against the fountain itself.

1976 [the book]

Perhaps the fountain’s most strident critic was one Cornelius O’Donovan, a Portland-based real estate agent and noted crank according to The Oregonian, which once devoted an editorial to his frequent letters to the paper. On at least three occasions in 1936, O’Donovan wrote to the Portland City Council and Commissioner of Parks, J.E. Bennett, demanding that the fountain be removed as “a hazard to traffic and time,” a “fossilized stag” that had “outlived its usefulness,” a “frightful, dangerous… gargoyle quadruped… a hideous eye-sore… howl[ing] for elimination.” In 1937, Bennett, by then Commissioner of Public Affairs, declined O’Donovan’s demands, saying simply that there was “no emergency which would warrant the appropriation of funds” for the fountain’s removal.

In a recent post on his Portland Architecture blog, local writer Brian Libby suggests that the elk’s main message might be about humility, “our humility, before the natural world. The bronze elk statue in the middle of Oregon's biggest city is a kind of reminder, just like seeing Mt. Hood, that living here we are closer to the forests and beaches than most urban denizens. For a lot of us, it's a big part of why we live here.”

Under the Thompson Elk’s Gaze: 120 Years of Protest

Click here for historian Milo Reed’s more in depth look at the social history and context of key protests at the Thompson Elk Statue.

Click here for list of protests over the decades.

Share with historian Milo Reed your experiences of enjoying—or acts of free speech around—the Thompson Elk Fountain on Facebook and Twitter

Lownsdale Square and the Thompson Elk Fountain have served as a backdrop for dozens of political protests, rallies, and controversial speeches, and much spirited discussion since the fountain was placed next to the park in 1900. While the tone and tenor of politically motivated action changed over the course of the 20th century, this space was always used by Portlanders to push, and occasionally exceed, the bounds of what the state considered to be acceptable free speech since the fountain was christened in 1900 and government buildings and a union hall arose around it.

Anti-war day gathering on SW Main St, Police Historical Archival Investigative Files - Red Squad

A follower of early feminist, Margaret Sanger, passed out pro-birth control flyers (and got arrested) in 1916. Communists staged a 1931 protest, 2,500-strong, against the deportation of nine of their own. Outraged African-Americans in 1975 rallied against the Portland Police Bureau’s shooting of a 17-year-old Black kid in the back of the head. County workers rallied for better pay in 1980. All of these actions, and many more, came before the Occupy filled the parks and street in 2001 and the protests against the murder of George Floyd, and subsequent clashes with Homeland Security forces, in 2020.

In July 17th 1921, a writer neatly summed the space in The Oregonian’s “Listening Post” column: “You can get into any kind of argument at Lownsdale Square. In the olden days the Roman, shrewd judges of human nature, provided a forum as a safety valve for their population. In London, Hyde park is the place where the public airs its views and grievances. In New York and other large American cities they have spots set aside for public debate. Portland’s safety valve is in Lownsdale Square and here they come to blow off pressure.”